ORANGE

SHIRT DAY

Orange Shirt Day, observed each year on September 30th, commemorates the children taken into residential and boarding schools in the U.S. and Canada. It is a time to honor the children who never returned home from these institutions, and to recognize the survivors and families who still carry this history.

It is both a day of mourning and resilience, and a reminder that the legacies of these policies still reverberate through Tribal communities today.

Orange Shirt Day

Orange Shirt Day is observed annually on September 30th to honor and commemorate the Indigenous children who were taken from their homes and forced into residential and boarding schools in the U.S. and Canada.

The day takes its name from the experience of Phyllis Webstad (Northern Secwpemc), who at the age of six had her new orange shirt taken away on her first day at a residential school. That shirt came to symbolize the stripping away of identity, family ties, and Cultural belonging that Indigenous children endured at the hands of American and Canadian colonial violence.

Today, Orange Shirt Day is a time to remember the children who were never returned home, to acknowledge the survivors and their families, and to affirm that “Every Child Matters.”

It is also a call for truth, justice and healing – reminding us that these events are not distant history, but living legacies that shape Indigenous communities today.

The Indian Boarding School Era

In the United States, the Civilization Fund Act of 1819 laid the groundwork for what became known as the Indian Boarding School Era. By the late 1800s, hundreds (eventually 367 in the United States) federally and church-run schools operated with the express goal of assimilation under the slogan: “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

For nearly 100 years, Native children as young as four were taken from their homes, stripped of their hair, clothes, languages, and names, and involuntarily placed into military-style institutions. Within these schools, children were forced to convert to Christianity and undergo complete assimilation into Eurocentric and settler-colonial ways of life.

Speaking their Native language or practicing traditional Culture was met with punishment, and many children experienced severe physical, sexual, and spiritual abuse. An untold number of Indigenous children were lost forever to these institutions, their bodies buried without record or return, leaving generations of families in mourning and uncertainty.

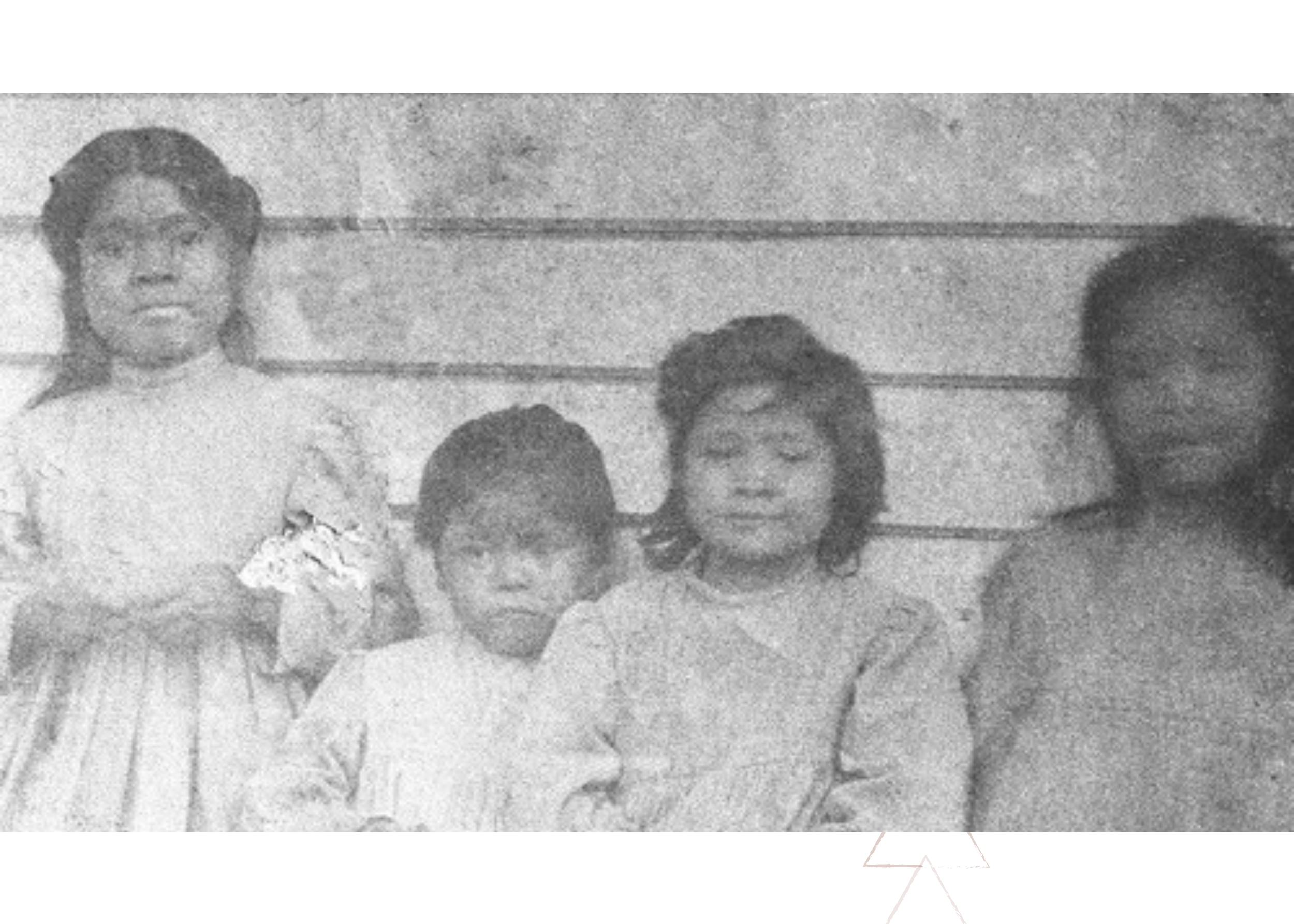

Nisenan Uncles at Greenville Indian Boarding School

By 1926, nearly 83% of all Indigenous school-aged children in the U.S. (over 70,000 children) were in boarding schools. These policies created enormous ruptures in Tribal family systems, leading to the widespread loss of languages, traditional lifeways, and generational knowledge. Such policies were not only acts of Cultural erasure; they meet the United Nations’ definition of genocide.

EVOLUTION TO ADOPTION ERA

The end of the Boarding School Era did not mean the end of assimilationist child-removal policies. Beginning in the 1950s, the Adoption Era saw Native children placed in non-Native foster and adoptive families at staggering rates. By the 1960s, one in four Indigenous children lived apart from their communities. This practice continued to sever Cultural ties as effectively as the Boarding Schools.

The Adoption Era was just as insidious as the boarding school system before it. It placed Native children in non-Native homes where their identities were erased through silence, rather than overt punishment.

Many of today’s Tribal Elders grew up in these households, separated from their languages, traditions, and kinship networks. For countless adoptees, the result was a lifelong struggle to understand where they belonged, neither fully accepted into Western society, nor connected to their Tribal communities.

These removals fractured not just families, but entire Tribal communities, perpetuating the goals of assimilation and Cultural genocide under a different name.

NCR Tribal Chairman Richard Johnson was adopted by a non-Native family at the age of two

NISENAN AND ASSIMILATION POLICIES

For the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe, the Boarding School and Adoption Eras left deep scars.

Many Nisenan children were sent to the Greenville Indian School in Plumas County (open 1890-1920). When Greenville Indian School burned down, they were relocated to the Fort Bidwell Indian School near the California-Nevada border.

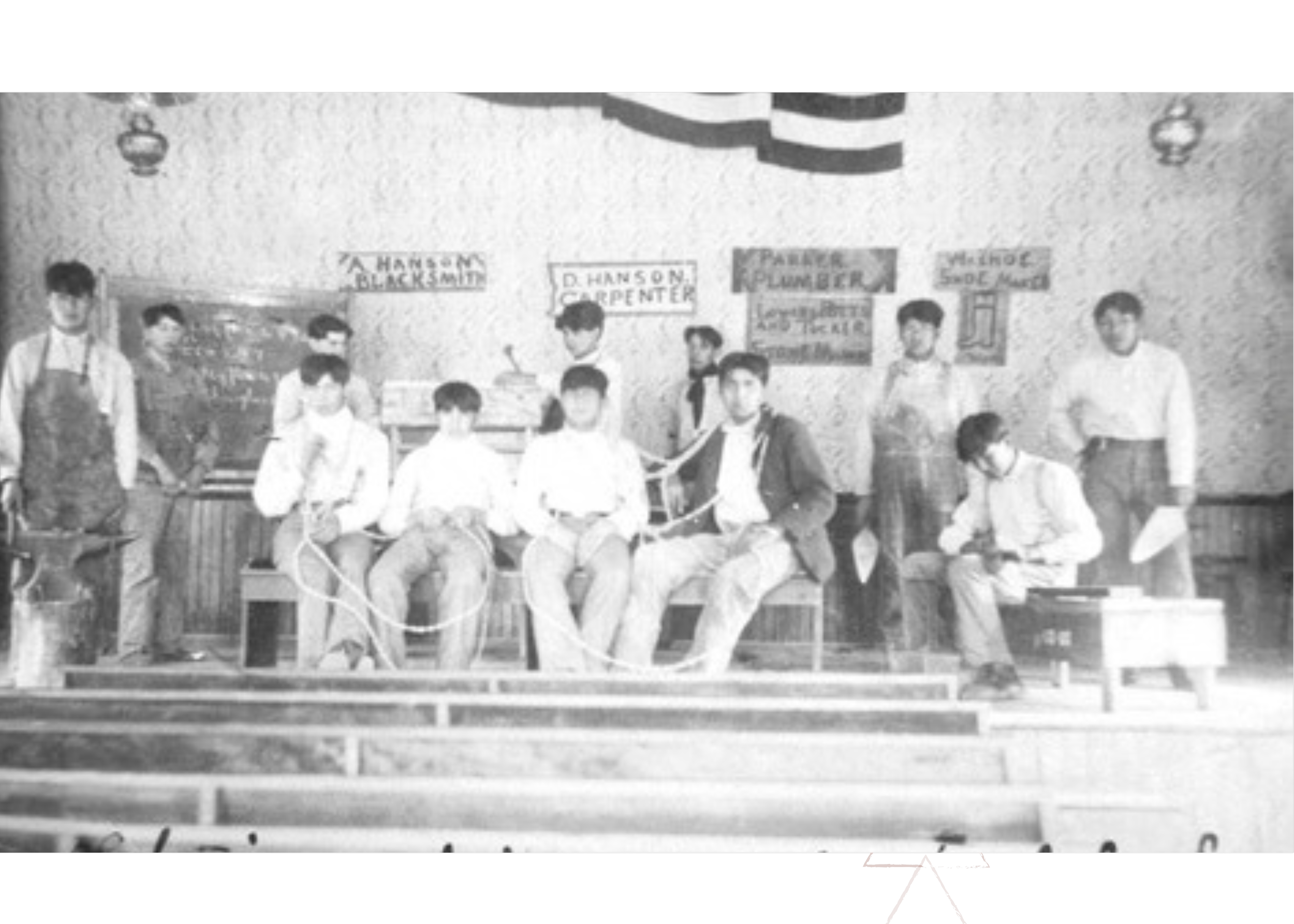

Others were taken even farther from their Ancestral Homelands. David Hanson, son of Henry Hanson and Mary Potts Rose, was sent to Haskell Indian School in Kansas and never returned home. David’s family was never told how he died.

NCR Tribal Chairman Richard Johnson was adopted into a non-Nisenan family at the age of two. Many other Nisenan families still carry stories of their grandparents’ terrors as they hid from Indian agents, or memories of those who were taken and never returned home.

Headstone and Residential School Enrollment Records for David Hanson

These removals that disrupted families and tore children away from Nisenan Homelands and lifeways are not distant history. Rather, the Boarding School Era and Adoption Era directly touched the lives of current Tribal Elders and continue to impact the lives of NCR Nisenan Tribal members.

“Grandpa Dutch”, Lorena Davis, Nisenan Tribal Council Member, VTA 2022

“My father was taken from his home to the Indian Boarding Schools when he was 5 years old. He was robbed of his childhood, family, and home, but mostly of his identity.”

Lorena Davis, Nisenan Tribal Council Member

“Keep Still and Be Quiet”, Cindy Buero, Nisenan Tribal Member, VTA 2022

“At the age of two, my mother was left without any family, completely alone. This was in 1923 in the town of Ione.

A small family of two, a sister and brother, took my mother in and raised her. Mom would refer to them as Aunty and Uncle Sam, they were Southern Nisenan, Miwok, and Black.

In 1925 the government sent Indian agents out to reservations to "gather up" Indian children and take them away to the Indian Boarding Schools and my mom was sure to go. Aunty yelled for Mom, "Ani 'To' O' Pe! Get under my skirt," then said "keep still and stay quiet" and with her baby doll, my mom did just that.

Growing up, I heard this story numerous times but not until this project did I ever feel the story. I can't imagine the fear running through the two of them. If found, Mom would have been taken away, and because Aunty and Uncle Sam were not white, who knows what punishment they may have endured?

Cindy Buero, Nisenan Tribal Member

“In the mid-1940s, Auntie Marianne was taken from our family when she was just over a year old. She was sitting in her playpen when people – likely county social workers – came into the house unannounced and took her. My grandmother, Carmel, tried to stop them, but she was threatened that if she resisted, all of her daughters would be taken.

Growing up, my mom, dad, and aunties were always on the lookout for Marianne wherever we went, scanning every crowd in case we might recognize her.

Many years later, she found her way back to us and was able to reclaim parts of her family and Cultural identity that had been stolen from her.”

Shelly Covert, Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribal Spokesperson

Each story of survival and loss echoes across generations, and is a reminder that the trauma of these devastating policies is not confined to the past – it lives on in the collective memory of the Nisenan, in the lived experiences of Tribal members today, and the impacts it has had on the Culture and Tribal identity.

Recognizing the violent legacy of the Boarding School and Adoption Eras is essential, not only to honor those who were taken, but also to confront the ongoing impacts of genocide and to support the Tribe’s path towards healing, justice and restoration.

Indian Child Welfare Act

The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978 was accomplished thanks to decades of advocacy by Indigenous communities fighting for Native children to remain within their families and Tribal communities. It is a protective legal outcome rooted in Indigenous resistance.

As legislation posed in direct response to the Boarding School and Adoption Eras, ICWA is intended to stop the mass removal of Indigenous children from their communities and ensure they are not systematically adopted into non-Tribal households. Instead, ICWA establishes placement preferences that prioritize extended family, Tribal members, and other Native families, recognizing that a child’s well-being is inseparable from their Cultural and community connections.

ICWA is intended to hold state agencies accountable. It requires that providers identify whether a child is Indigenous and make extra efforts to keep children within their kinship and Tribal systems. Historically, Western social workers and service providers have not protected Indigenous children. Too often they have been the active agents of removal, and continue to deny Tribal communities access to CPS-impacted Tribal youth today. Without ICWA, child welfare agencies would continue to adopt Indigenous youth to non-Tribal families under the same assimilationist logic that fueled the Boarding School and Adoption Eras.

While ICWA is an important safeguard, it is also inherently constrained. It is designed to protect Indigenous children, but it is still a tool operating within colonial systems that cause the harm it attempts to address. Native children are still disproportionately removed from their families, and ICWA itself continues to face challenges at the Supreme Court level.

Protecting Native Children, Strengthening Tribal Communities

True protection of Native children means strengthening family and community systems so children can thrive. The often-cited reasons for removing children from families, including substance use, poverty, and “abandonment”, are symptoms of genocide survival and historical trauma.

Even when harm exists within a family, children remaining within their kinship networks keeps Tribal communities stronger. In many cases, aunties, grandmothers, and cousins step in to care for children when the immediate household is struggling. When children are taken outside of the community, these natural systems of care are disrupted, weakening the Tribal community itself.

Addressing these issues through family-centered and Tribally-led programs, such as substance use disorder support, mental health services, and community wellness initiatives, provides the best way to keep Native children safe while maintaining the strength of their kinship ties. Prioritizing family preservation and investing in Tribal community wellness are not only acts of restorative justice, but also acts of protection for both Indigenous children and Tribal communities.

Lasting Impacts

Of the residential and adoption eras

The intergenerational impacts of this history remain clear.

For individuals, the Boarding School and Adoption Eras resulted in the loss of identity, self-esteem, and a sense of safety, leaving many institutionalized and struggling to form healthy relationships. Within families, these policies stripped away parental authority and fractured extended family systems.

For Tribal communities, they severed language, traditions, and ceremony, and for Tribal Nations, they weakened governance structures and reduced population through both loss of life and declining Tribal membership.

Across all these levels, survivors and their descendants carry disproportionately high rates of PTSD, depression, substance use disorder, suicide, and chronic illness. These conditions have been shown to be both socially and biologically linked through the impacts of intergenerational trauma and epigenetics.

The devasting impacts of these policies on the individual, family systems, and Tribal communities, are recognized by scholars and Indigenous communities as Cultural genocide. They inflicted a profound “Soul Wound” – a spiritual injury and ancestral trauma that continues to reverberate through generations.

Healing the Soul Wound

Yet Indigenous communities also emphasize that healing from the lasting impacts of the Boarding School and Adoption Eras is possible.

Healing the Soul Wound requires more than acknowledgement. It involves a return to Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and relating. The process of healing from intergenerational trauma is inseparable from reclaiming Cultural traditions, language, storytelling, and ceremony.

Central to this healing is the protection of children and keeping them within Tribal families, where kinship networks of aunties, grandmothers, cousins and extended relatives provide care and stability. These family systems, disrupted by colonization, are themselves medicine, grounding children in identity, Culture, and belonging.

Healing also means cultivating strong community connections that can counter the dis-ease of colonization. The violence, substance use, poverty, and family struggles often cited as reasons for child removal are symptoms of genocide survival and historical trauma. By addressing these root causes through Tribally-led wellness initiatives, language and Cultural revitalization, and community-based care, the Soul Wound can begin to mend.

Intergenerational Tribal Members gather at the recently rematriated Yulića

Indigenous communities affirm that healing is most effective when it is community-centered, grounded in Cultural practices, and honors the resilience and wisdom that sustained Indigenous peoples through these centuries of colonial violence.

The reclamation of language, ritual, and Cultural identity are not just symbolic acts – they are essential forms of medicine.

CHIRP’s APPROACH

All areas of CHIRP’s work and mission is informed by this understanding that Cultural revitalization, community connection, and Tribal identity are the medicine for healing the ongoing harms of colonial violence.

Tribal Youth programs create safe spaces for learning and wellness grounded in identity and connection to land and community.

Tribal Community Wellness initiatives address intergenerational trauma by centering relationship building and Cultural reclamation.

The rematriation of Yulića offers not just LandBack, but a space for Cultural ceremony, planting, and gathering on Ancestral ground.

Arts enrichment and Cultural revitalization projects return song, stories, and skills to Nisenan Tribal members, while language revitalization restores a voice that colonization tried to silence.

Supporting CHIRP’s work, through participation in the Ancestral Homelands Reciprocity Program (AHRP), advocacy, and informed allyship, are ways to walk in aligned action.

Each contribution helps create pathways of healing from the legacies of colonial violence, including the Boarding School and Adoption Eras, by uplifting the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe’s journey of remembrance, resilience, and restoration.

Reflection

And Call to Aligned Action

Orange Shirt Day is not only about remembrance. It is also a call to aligned action.

Nearly every Indigenous family in the U.S. has relatives who were directly impacted by the boarding schools. These legacies are not distant history. They are the lived reality shaping Indigenous communities today, including the Nisenan.

As allies and supporters, we encourage you to reflect on your own relationship to this history. Ask yourself:

How do I benefit, as a settler living on unceded Indigenous lands, from the systems that displaced Native children and communities?

What steps can I take to learn the truth about the erased history of the boarding schools and share it with others?

How can I advocate for justice, healing, and accountability in my community and at a national level?

Concrete Ways to Engage in Aligned Action

Educate yourself and others about the U.S. Boarding / Mission school system, not just the better-known Canadian history

Support Indigenous-led healing efforts, including language and Cultural revitalization programming

Advocate for the full implementation and protection of ICWA, and keeping Indigenous children with their families and Tribal communities

Build Reciprocal relationships with the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe and other Tribes

Advocate for the protection of Tribal sovereignty

On Orange Shirt Day, we commemorate and remember the children who never returned, the survivors who carry these memories, and the families and Tribes forever changed.

It is also a day to honor the resilience of these communities, and affirm that healing and justice are possible when we commit to truth-telling, collective healing, and accountability.

We are reminded that to honor this day, we are called not only to reflect and learn, but to walk forward in aligned action – supporting healing, justice, and restoration of Indigenous Cultures and communities.

“Rightful Return", Saree Robinson, VTA 2022